Additional materials about blended learning

Publication date: 19 Sep 2024

This Resource Hub was created by QAA Scotland, College Development Network (CDN), Education Scotland and sparqs (Student Partnerships in Quality Scotland) to support the tertiary sector to plan and deliver programmes that embed an active blended learning approach.

This resource is one of the outputs from the cross-sector project - The Future of Learning and Teaching: Defining and Delivering an Effective and Inclusive Digital/Blended Offering.

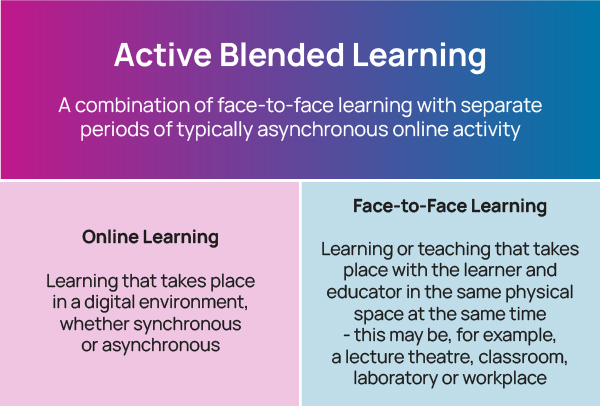

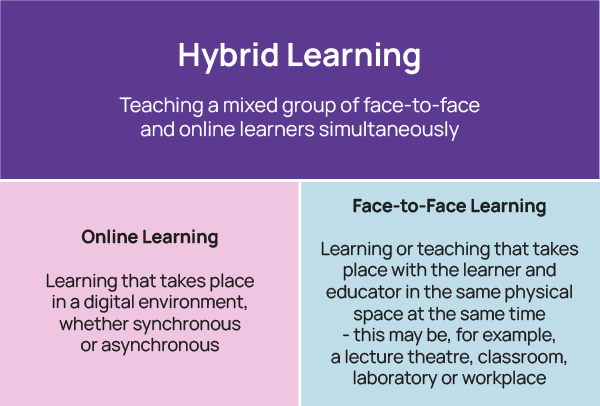

There is considerable confusion around definitions and terms associated with blended learning. For example, sometimes blended can be referred to as ‘hybrid’ (Jisc 2020). The visual diagrams below contains the definitions and terms used throughout this Resource Hub.

Blended learning is typically a combination of face-to-face learning with educators and learners gathered together in the same place, combined with dynamic digital online activities (often asynchronous) such as quizzes and discussions, and links to rich online content including recorded lectures (Jisc 2020).

The concept of blended learning in tertiary education is not new - it was first used in 1999 in a press release by EPIC learning in Atlanta (Friesen 2012). Blended learning has always been delivered in varying degrees of ‘blend’ reflecting the evolution of the term over the last two decades (Jisc 2023; Alammary et al 2014).

Blended learning has been growing in popularity, providing an effective flexible approach for an increasingly diverse student population whilst offering meaningful opportunities for peer-to-peer and learner-to-educator interactions (Cleveland-Innes and Wilton 2018). The widespread adoption of the term ‘blended’ has led some to assert that all learning has the potential to be blended (Jisc 2023).

Although blended appears to be a simple idea, it is highly complex because there is no definitive right ‘mix.’ The ‘mix’ will depend upon a variety of factors including the educational setting, the intended learning outcomes and the underpinning pedagogical approach. As a result, there are many versions of blended and many ways to approach planning for blended learning (see Section 3).

To avoid the risks of blended and galvanise the opportunities, educators need to focus upon the planning and delivery of the blend for improved learner outcomes (Jisc 2023 and Jisc 2020). We can conceptualise blended learning as on a continuum, with educators planning the right blend for their specific context and cohort of learners, deciding how much face-to-face synchronous on campus is required and how much learning can be supported in the digital sphere, but always with a focus on ensuring that learning is active. Chickering and Ehrmann (1996) remind us:

Learning is not a spectator sport. Students do not learn much just sitting in classes listening to teachers, memorizing pre-packaged assignments, and spitting out answers. They must talk about what they are learning, write reflectively about it, relate it to past experiences, and apply it to their daily lives. They must make what they learn part of themselves.

Dr Neil Gordon recalls that the emergency pivot to online learning in 2020 due to Covid was often underplanned and implemented quickly, with limited educator development compared with planned and designed blended learning. Now with Artificial Intelligence (AI) in tertiary education, Dr Gordon states that it is more vital than ever that we prepare and design for quality active blended learning.

"The swift transition to online learning in 2020 showcased the education sector's ability to adapt rapidly to emergent circumstances. In tertiary education, this shift saw a large-scale move from in-person to digital and distance learning, though it was executed hastily with minimal preparation, leading to questionable content quality and a lack of sustained commitment. As students returned to campuses, the chance for implementing blended learning arose; however, institutions often reverted to pre-pandemic methods where online resources merely supplemented traditional education. With the advent of AI in education, it is now crucial to provide educators with the support and guidance necessary to design and implement high-quality blended learning that effectively integrates digital activities with face-to-face instruction."

Dr Neil Gordon, University of Hull, 2024

Further materials on blended learning, including principles and an exploration of potential opportunities and risks, are available in the resource below.

Publication date: 19 Sep 2024

Active learning is a popular approach, aiming to engage students in the learning process through participatory individual, pair and group activities. It should underpin any implementation of blended learning. As Tab Betts (2022) states:

In active learning, rather than teacher ‘transmitting’ knowledge through lectures or reading, learners engage in a series of activities which require them to produce observable evidence of their learning. Where possible, these individual, pair and group tasks should aim to develop higher order thinking skills [and] emotional connection with content.

Tab Betts's video about the benefits of active learning provides practical examples and extensive evidence - this is a clarion call to move away from transmissive education.

Active blended learning should lead to deeper learner understandings and retention of knowledge as well as fostering higher-order thinking skills, especially reflection.

Active blended learning describes a programme of blended learning that includes active learning throughout its face-to-face and online components.

Active blended learning has four main characteristics:

In the document below, Tab Betts from the University of Sussex discusses Active Blended Inclusive Learning.

Publication date: 19 Sep 2024

In Section 2, we call upon Simon Thomson’s work on ‘conscious modality’ to inform our thinking when preparing for active blended learning. He urges us to think 'more deeply and purposefully' about the different approaches that we use and the contexts we use them in.